The difference between economic growth, and economic growth for all

Economic policy is always boring, until it’s too late. Pensions. How they are funded, who they cover, what happens if they fail. Boring. Until it was too late. Mortgages. Who has them, who needs one, who should have one. Boring. Until it was too late. Finance. Capital markets, their products, their structure, their risk profile. Boring. Until it was too late. You see the point I’m making.

The difference between economic growth, and economic growth for all

It’s easy to look away from numbers. The data doesn’t necessarily tell us an obvious story. And then one day, a catalyst sparks an unforeseen, if, with hindsight, predictable event, and we all wonder why we didn’t see it coming.

Something similar happened with the Brexit vote. Of course, it was a perfect political storm: an overconfident Prime Minister calls a referendum that he only needs to have to pay off his right flank, safe in the knowledge that the mainstream voters and the leadership of the Labour party will carry him through. Except he forgets that there is someone more despised than even his right flank: him.

But beneath all of that, the Brexit vote revealed a divided country. Between those who felt that Britain as it was before the referendum offered them a decent enough – if imperfect – future, and those who felt it offered them nothing of the sort.

Could we have seen it coming? Perhaps we could. Take two graphs.

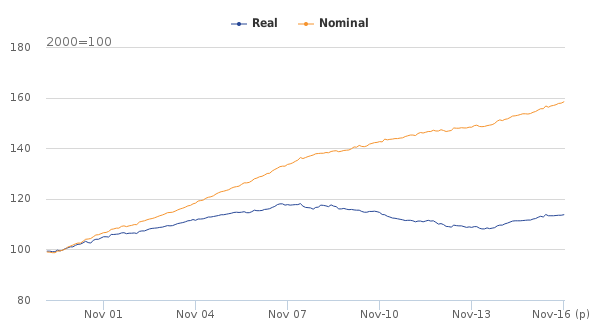

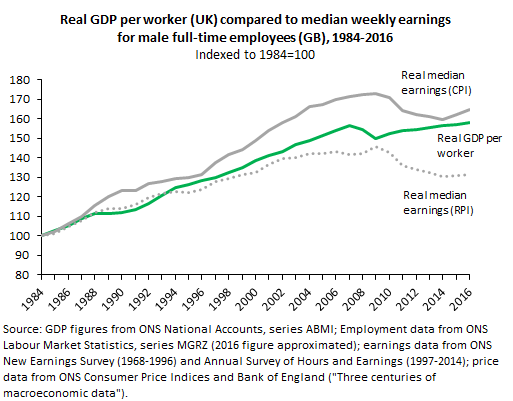

Real wages are still, today, on average below what they were in 2008, nearly a decade ago. At the point of the referendum, average wages were yet to return to the level they hit eight years earlier. The difference between real and nominal wages is inflation. People have watched prices steadily drift up while their wages have remained stubbornly flat. Not an overnight shock, but a long drawn out crisis all the same.

It is important not to overinterpret the data with hindsight. After all, vast numbers of pensioners (over 60 per cent of them) voted to leave the European Union, and pensioners incomes have not seen the same fall as incomes for the working age population (in fact they rose by 19 per cent in real terms in the last 10 years). But there are nearly 32 million British people of working age. That surely should have been enough to carry the vote, had far too many people not had too little reason to back the status quo.

So in the years running up to the crucial Brexit vote, the economy was, by and large, moving ahead. But in the case of the most crucial, most noticeable, economic transfer – a person’s wages – the economy was not moving ahead at all. In fact between the crash and the 2015 general election wages largely only fell, and since then, pay has struggled to make up ground, against a picture of an otherwise ‘growing’ economy.

Worst of all – nearly 4 million households in measurable (and therefore known) poverty include someone at work. Of the 17 million Brexit voters, for all of those wealthy retired voters who always hated Brussels, how many were unpersuadable simply because they had too little to lose, and couldn’t stand Cameron.

The problem with all this though, and the reason we didn’t see it coming, is that no one’s life is a graph. I mean, we are all data points on the graph. But no one feels like a data point. Everyone feels like a person. And people are notoriously bad at providing logical, graph-like, mathematical reasons for their political judgements. ‘My individual wages have failed to keep pace with growth in the economy at large’ said no person on no doorstep, ever. Unhappiness with what is on offer manifests itself in lots of different ways but it isn’t likely to be an analysis of the macro-economy.

We all know of course that people are much more likely to connect with politics (and politicians) emotionally. That is how we make our choices. Our emotions are informed by the facts of our life and are responses to the facts we experience, the facts we see. So, whilst the graphs above cannot tell us all we need to know about how the mainstream Labour and mainstream Conservative parties lost the Brexit vote, they tell us about some facts likely to impact on the choices we make.

The challenge is to work out how, and if, changing the trends shown on the graphs above can be sure to impinge on the lives of the many in our population who lost out over the past decade. How should policy makers have seen the separation of economic growth from economic growth for all? And what can be done to repair the link?

This challenge is what is meant by creating ‘inclusive growth’. Or as I think of it, making sure there is a hard chain linking growth in the economy overall to the growth of wages and incomes of the many.

When the country rises, so must all within it.

The hard links in the chain are what should have kept our country together. They are the rules of the economy that should have meant that the British economy doing better meant individuals, families, towns, cities all doing better too. You can see from the graphs above that the rules worked between 1997 and about 2005. Our country grew, and we all grew in capacity with it. But then the model stopped working. And 11 years later people were asked to vote for the status quo, even though the status quo was clearly failing the many.

So that’s why we have to work out what the rules of the game should be. We will never be able to see the trends until it is too late. We need rules that shape our markets, including the labour market, that will achieve the outcome that people can see and feel in their pockets. Analysis of the past is only any good if it can help shape the future, and understanding the graphs, the macro-economy, the big numbers, is only any use if you can see the connection between that and life as experienced by British people in every town in our country.

It’s not enough to say that somehow our economy is rigged against people, as if this was one great fiddle. Rather, we should remember that policy choices have consequences.

Now some people suggest that the correct response to falling wages, and precarious work, is some sort of universal benefit, or citizens’ income. Recent Fabian Society research demonstrated that the vast majority of people – about 80 per cent – feel positive about their work even despite the story told here about wages. So even if it were practical for government to increase tax and then to transfer something in the region of the state pension to every person in our country, costing hundreds of billions, it hardly seems like it would be popular.

So if people, in general terms, actually like their work, the problem is making sure they get paid enough and can get promotion. Start from the alternative view that working people are ground down by their experience of work, and our policy ideas will fail to resonate. Rather, recognise what the past decade has taught us: that the growth of the economy must mean economic growth for all within the economy, or else there will be consequences.

So, the question remains: what are the hard links in the chain between the economic growth of the country as a whole and economic growth of the people, families and towns within it?

Unfortunately, this is where the boring stuff still matters. You can get paid more if you have better prospects. That means a buoyant labour market, and the skills to participate in it.

Now the government say that they are addressing the challenges in our economy by investing in infrastructure, through their plan to develop an industrial strategy. And along with buzzy new ideas like universal basic income, everyone in politics loves announcing campaigns for new railway lines (me included). Trains are big, fast, expensive and showy. But travelling to work by train tends to be the preserve of those who already have a high-skilled job and are commuting some distance. We should worry a little more about those who get the bus to work, or we will fall into the same trap as before, just focusing on those who already have a chance to get on. As I mentioned above, in politics we seem permanently in danger of missing the point.

For example, take those who work in low-pay sectors like care, retail, hospitality, or construction. Each sector has its own challenges, but one thing that unites of all these sectors is the likelihood of people working in them to be working below their potential skill level. Hopefully our new metro mayors will be able to take on some of this challenge, and provide better education opportunities for those at or near the minimum wage. But what about in those areas without mayors? Do they fall even further behind? Skills transfers matter much more for future growth than a massive financial transfer like universal basic income.

And in case anyone should think that I have forgotten, with less than 15 per cent of people in the private sector represented by a trade union, it is little wonder that workers have insufficient power to command better wages. Our labour market leaves too many people on their own, without the strength of collective bargaining to get them a good deal.

Universal basic income fails for another crucial reason. It would fail for the same reason that tax credits were economically effective but open to political challenge. For most people, the part of government, of the state, that they wish to defend are the things they can see, they can touch, emotionally engage with. The hospital their child was born in, that cared for a sick parent, the school they went to, the park they played in with their grandchild. They prefer to earn their wages, and do a job they enjoy. Transfer payments from the state are always harder to defend, as the history books attest to (child benefit, for example), because the institutions of the state that persist – that are, in the end, fought for – are those that engage emotionally with the public.

So for me, truly inclusive growth means making the most of the institutions we already have – colleges of further education for example – and building new ones like universal quality childcare. Many members of our workforce are prevented from returning to work after the birth of a child, simply because the cost of childcare means it is not worth it or even possible. This affects mostly women, who often shoulder the main burden of childcare. Universal free childcare would provide the economic and social infrastructure to allow many more women to go back to work or have the time to gain more skills, should they want to. Moreover, good quality childcare would benefit all of our children, narrowing the attainment gap by providing our children with the preparation they need to succeed in school. The hard links in the chain, ensuring that growth in Britain necessarily involves economic growth of all of those people and places within it, are, in fact, the institutions of the state.

These are the platforms Labour governments have built for ordinary people to stand on from which to reach up. But these are the very institutions under attack from current government policy. If we’re going to rebuild the chain then the government must change tack. We need to develop new ideas and solutions and the APPG can be a place to bring people together across the party divide. Theresa May has spoken about an economy that works for all. Now’s the time to protect the institutions that can deliver that economy and inclusive growth, before it is too late.

Alison McGovern MP, Vice-Chair of the APPG on Inclusive Growth, Labour Member of Parliament for Wirral South

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply