Globalisation and Inclusive Growth: the challenges for governments and business

The current rise in populism internationally reflects in part the inability of governments to address adequately some of the big challenges arising from globalisation. The planet is effectively shrinking as the digital economy cuts across old frontiers and challenges the old orders that divided the world into developed and developing nations. Whilst globalisation brings substantial benefits, there are also some significant disadvantages. The low-waged in relatively rich developed nations have se

Globalisation and Inclusive Growth: the challenges for governments and business

Those affected have been described euphemistically as ‘left behind’. It is not the case that global liberal elites have wilfully ignored this looming problem. Indeed, there have been attempts to help the low-waged, tax credits with a minimum wage in the UK and America’s efforts to provide healthcare for the poorest being two primary examples. However, these are palliative policies which have not addressed some of the underlying causes of disadvantage and the consequent rise in inequality. Many countries have actually missed the opportunity to effectively include more of their populations in their economic growth.

We must take seriously the social frustrations increasingly being expressed through the ballot boxes of successive elections and referenda. In a poll of voters in December 2016, ComRes uncovered something of the strong negativity that some in the UK hold towards globalisation and the perceived effect this has had on inequality. Almost half (49%) of participants felt that globalisation has pushed wages down for British workers, while 51% thought that it had led to more inequality between rich and poor.

This was a key theme at this year’s annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF), where a new report was launched on ‘Inclusive Growth and Development’. This report includes the Inclusive Development Index (IDI) which measures 109 countries for inclusive growth. Out of these, 30 are considered within the sub-index of advanced economies. The UK ranks at 21st just above America at 23rd with many Southern European countries being ranked below. The marked difference is the Scandinavian region of Europe. At the top of the IDI is Norway, with Sweden 6th and Finland 11th.

OECD data also shows that income inequality in Scandinavian countries is dramatically lower than that of the UK. While the UK had a higher level of income inequality (36%) than most European countries in 2013 (based on the Gini coefficient for disposable income) Norway was the second lowest amongst OECD countries at 25%, with Finland at 26% and Sweden at 28%.

As we can see, public frustration is valid. Income distribution in many countries is unequal, and growth in advanced economies has not translated well into social inclusion, but this is due to a lack of attention rather than ‘an iron law of capitalism’. As the WEF report highlights, wider inequality in our current financial system needs to be recognised and addressed to restore public confidence in the capacity of technological progress and international economic integration to support rising living standards for all.

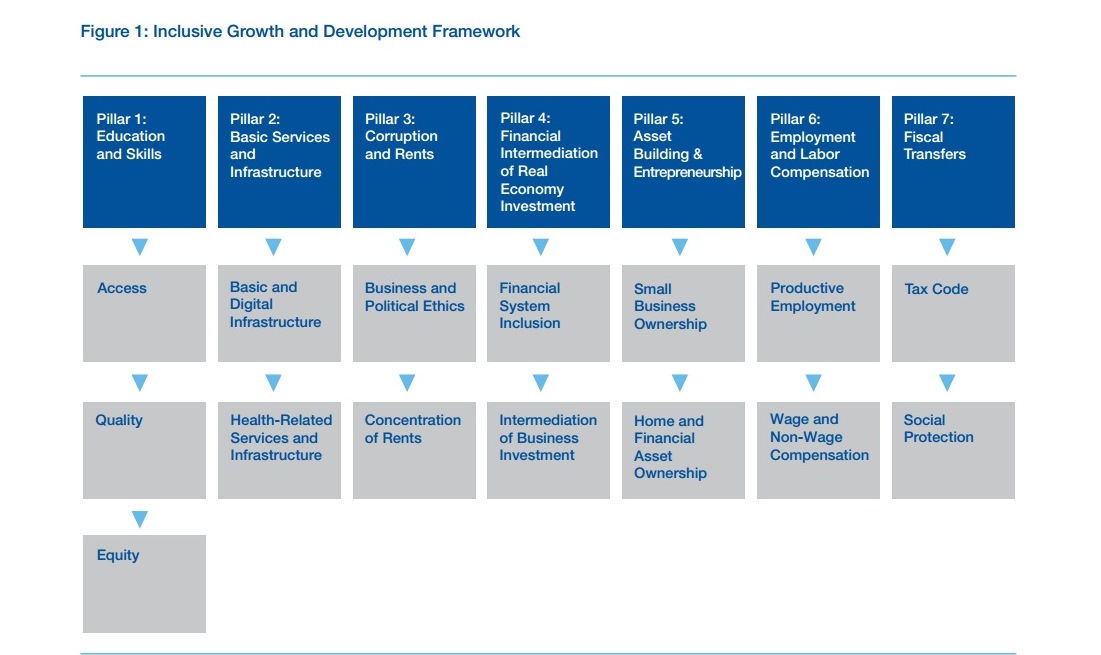

The report presents an interesting policy framework encompassing seven principal domains (pillars) and 15 sub-domains (sub-pillars) which describes the spectrum of structural factors that particularly influence the breadth of social participation in the processes and benefits of economic growth factors. As a whole these represent an ecosystem of structural policy incentives and institutions to help diffuse opportunity, economic security and quality of life. Below is a figure generated by the WEF for the report.

This model of inclusive growth was described as one which is both pro-business and pro-labour, an agenda to boost social inclusion and economic efficiency through a stronger focus on appropriate institutions. If the institutions in society are weak and old fashioned they will not be able to make the adjustments to a fast moving world or ensure that those entrusted in their care are well protected and equipped for global challenges. For example, if the education system fails to ensure computer literacy, a whole generation of schoolchildren will grow up digitally disadvantaged. If basic labour standards fail to keep pace with technological changes and are too inflexible to support rising productivity and skills adaptation then a whole generation of workers will find themselves facing redundancy.

This report provides a fascinating snapshot of the world in 2017, but we must expect the challenges to intensify as the fourth industrial revolution strikes and new technologies threaten the old order. Again, taking the UK as an example, the Institute of Fiscal Studies in its report ‘Living Standards, poverty and inequality in the UK 2016’ highlighted that after 2016 income inequality is expected to increase. This growth in inequality between 2015/16 and 2020/21 is expected to reverse the fall previously seen between 2007/08 and 2015/16.

This is no doubt what prompted a Conservative British Prime Minister to consider tackling the emotive issues of wage multiples between the highest and lowest paid in organisations. However, to bring such changes about, governments will need to set meaningful targets for change to improve five key areas of human capital formation: active labour market policies, equity of access to good quality basic education, gender parity, work benefits and protection and better school-to-work transition. A universal basic income is no substitute for these five crucial institutional underpinnings of a well-functioning labour market and we must level-up performance across these areas.

So, we must fix our attention on the quality of growth and start clearly demonstrating to the ordinary man and woman on the street that our endeavours are focused on achieving greater fairness, shared inclusive growth and a sustainable future for all. We are being called to make a collective commitment to greater responsiveness and to take responsibility for economic leadership – this applies to both governments and businesses alike.

Rt Hon Dame Caroline Spelman MP; Vice-Chair of the APPG on Inclusive Growth and Conservative Member of Parliament for Meriden

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply