Welcome to the Future of Political Economy

The debate held amidst the snow-topped peaks of Davos this year was dominated by one issue and one issue alone, the surge in inequality. In a democracy, anger isn’t abstract. As both the vote for Brexit and the election of Donald Trump show, it turns up on polling day, with potentially disastrous results for the health of the world’s marketplace.

Welcome to the Future of Political Economy

In the US, new research shows that in the rust-belt states an incredible 40% of those born in 1980 are worse off than their parents. Here in the UK the gender pay gap still looms large – and as the Institute for Fiscal Studies revealed, there has been a four-fold increase in the number of men in low-paid, part-time work over the last 20 years. Young people in Britain, according to the Resolution Foundation, can now expect to be £12,000 a year worse off in their twenties, than the generation before them.

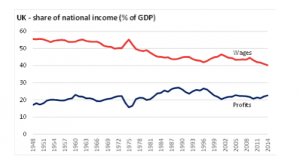

The root of the problem is what the OECD describes as the ‘productivity-inclusiveness nexus’; productivity growth, which is what drives standards of living, is flat. Wages as a share of national income are falling – and a bigger slice of the wealth that is created is carried off by those at the very top.

Today’s combination of hyper-loose monetary policy and tight fiscal policy means that the asset-rich get richer while the asset-and-income-poor get battered. If you’re lucky enough to own a house or shares or pension rights, you’ve done well since 2010: the stock market is up 40%; house prices are up by over a quarter; and the ‘triple lock’ on pensions in the UK will have channelled more than £33 billion extra to those with pension rights by 2020. Yet those on tax credits have seen their incomes fall precipitously while, of course, benefiting not at all from asset-price inflation; needless to say, they have little if any pension rights to protect.

Yet beyond the economics of austerity, it is now clear that the four basic assumptions that underpinned Anglo-Saxon political economy since the 1970’s – and the views of politicians like me – are now broken, and need rethinking wholesale.

Much was owed to Milton Friedman and the thinking of the monetarists. In the years after Friedman’s 1969 American Economic Association lecture, his ideas took hold; that huge levels of public spending, and public borrowing, crowded out private investment by driving up interest rates and inflation. The corollary was the small state, with low levels of corporate tax, designed to spur investment and job creation. Fierce competition in the marketplace would drive up productivity, and the ensuing wealth created would trickle-down – sometimes with the help of big fiscal transfers like tax credits – to enrich the majority of the population.

New Labour brought some important changes of approach to the Thatcher-Lawson years. New Labour recognised that demand management was important but could not on its own deliver high and stable levels of employment; it provided a new institutional framework for governing monetary policy including the independent Bank of England to replace the failed policy of target chasing; and delivered active supply side policy – targeting productivity, competitiveness and active labour market policy with policies like the new deal, tax credits, the national minimum wage – support for high levels of employment. Contrary to Nigel Lawson’s neat but contrived separation of macro-policy to combat inflation and micro-policy to aid competitiveness, New Labour argued that ‘macroeconomic and microeconomic policy are both essential – working together – to growth and employment’.

Figure 1: The UK economy produces high levels of inequality. Worse, wages as a share of national income are falling – while the top 1% carry off a bigger and bigger share (Source: Resolution Foundation; House of Commons library; OECD)

For mnny years there was much to the ‘constrained state’ theory. But those years are decisively behind us.

For mnny years there was much to the ‘constrained state’ theory. But those years are decisively behind us.

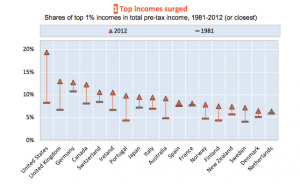

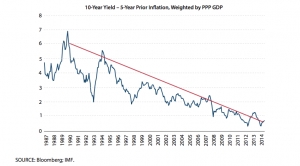

First, it is clear that large scale government borrowing is driving up neither interest rates nor inflation. As Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, Robert Gordon and Ben Bernanke have all argued – with different explanations – there is today vast global surplus of savings outstripping investment, and for as far as the eye can see, interest rates and inflation expectations are, historically, rock bottom, despite government debt in Western nations rising to 80-90 per cent of GDP.

Figure 2: The Evolution of Global Interest Rates

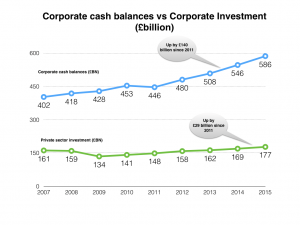

Second, it is no longer clear that slashing taxes and red tape do actually spur the sort of boost to investment that Government’s used to expect.

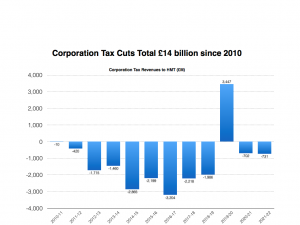

As Figure 3 sets out, since 2010, the UK government has delivered corporate tax cuts totalling some £14 billion. And private sector investment has risen – by around £29 billion; but cash hoarding by the private sector has increased an extraordinary five times more. An incredible £140 billion extra in cash (over 2011 levels) is now sitting in corporate bank accounts.

Figure 3: Corporate Tax Cuts and Private Sector Investment (Source: House of Commons library)

At the very least, we can conclude that government strategy for mobilising investment is significantly under-powered. When firms invest less, productivity stalls. And when productivity stalls, wages stall. The bottom line is this: the marketplace alone is no longer able to mobilise the investment society needs to drive forward economic progress.

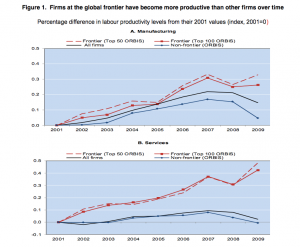

Third, it is no longer clear that in the new ‘platform economy’ dominated by new super-giants like Google, Apple, Alibaba and Facebook, productivity gains are diffused through the economy as free market theory would suggest.

Figure 4: Productivity Gaps Between Frontier Firms and the Rest (Source: OECD)

The globalisation of the last thirty years has sparked the most extraordinary $8 trillion merger wave, creating a vast new consolidation in the commanding heights of the global economy. These new Olympians channel billions into brand building and technology spending to create giant new barriers to competition; around 1,500 firms now control about half of world-wide R&D. The result is, as the OECD has discovered, that the productivity of industry-leading ‘frontier-firms’ is hugely ahead of the rest of the economy. And if productivity gains are ‘hoarded’ by a handful of firms, then only a handful of workers get well paid.

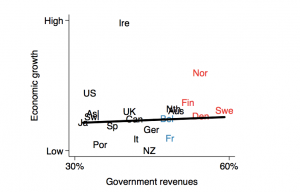

Fourth, it is no longer clear that ‘big states’ do indeed slow down economic growth. What Lane Kenworthy has called social democratic capitalism, may in fact be better for economic growth, because it ‘encourages entrepreneurship, facilitates employment by women and those from less-advantaged backgrounds, allows unemployed workers more time to reskill and choose a productive job, and limits income inequality’.

What is the evidence? Well, nations like Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden all have a tax take that is at the extreme end of advanced economies. And all have enjoyed above average levels of economic growth (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: ‘Big States’ do not seem to suffer slow growth (Source: Lane Kenworthy)

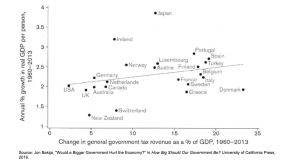

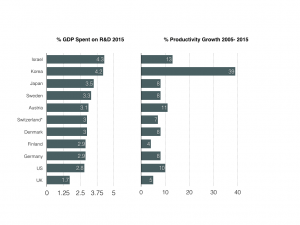

The issue is thrown into sharpest relief by those nations that spend most on research and development. There is more and more evidence that far from ‘crowding out’ private sector investment, public science spending ‘crowds in’. This appears to have a crucial effect on productivity growth. Some eight nations worldwide muster R&D spend of 3% of GDP. All bar Finland, have enjoyed productivity gains over the last decade that well ahead of the UK.

Figure 6: R&D spending and productivity growth (source: House of Commons Library)

So what does all this mean for the future of political economy? It must mean a much sharper focus on the institutions that shape the marketplace – and the rules that guide them.

As the late, great Nobel economist Douglass North proved, the quality of a country’s economic growth depends on the quality of its institutions. Look at Britain. As I argue in Dragons, my history of British capitalism, down the ages there would have been no British miracle if it wasn’t for great national institutions, like Parliament, the Royal Navy, the Royal Exchange, the Royal Courts of Justice, the Royal Society, and the welfare state first pioneered in places like Bournville, Port Sunlight and the board rooms of John Lewis..

Our challenge today is that the institutions needed to democratise the opportunities of this new global order simply do not work for ordinary working people.

For instance, we have global institutions that can help reflate growth – but we’ve not found ways of taxing the new wealth of nations: globally, $7.5 trillion is currently stashed in tax havens. Some $6 trillion of that has never been taxed. That is a problem when we need fiscal policy to carry more of the burden for driving up global demand.

Or, here at home, as many of the authors in this pamphlet point out, we lack the institutions needed for this new age. As Caroline Spelman, Alison McGovern and Richard Samans, all point out in this pamphlet, countries with better social institutions, like childcare services, technical education systems and systems that give working people access to assets like housing and pensions, do much better in creating inclusive growth.

New ideas in economics only come along every so often. And orthodoxy takes time to change. But, what is now clear is that the neoliberal orthodoxy of the past is collapsing into the dust. A new philosophy of inclusive political economy is starting to take shape. And that will be the meat of our debate for the rest of this parliament.

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply